Urban Design: Using Data in Urban Planning

/Technological advancements change the way we learn, the way we communicate, and the way we live. With an increasing amount of data available about our built environment and those who live in it, urban planners are discovering new ways to incorporate data into city planning and design. This week, our Project Manager Josh shared his thoughts on a recent lecture regarding the use of data collection for the advancement of city planning, and reflected on the potentials of data collection for architecture.

Written by Josh Janet, Project Manager | PE:

I had the good fortune to be able to take an Urban Form course with Professor Anne Moudon at the University of Washington two years ago. After 34 years with UW, Anne decided to retire, allowing more time for herself to travel the world and to focus more research in the Urban Form lab that she helped establish with the Department of Urban Design and Planning.

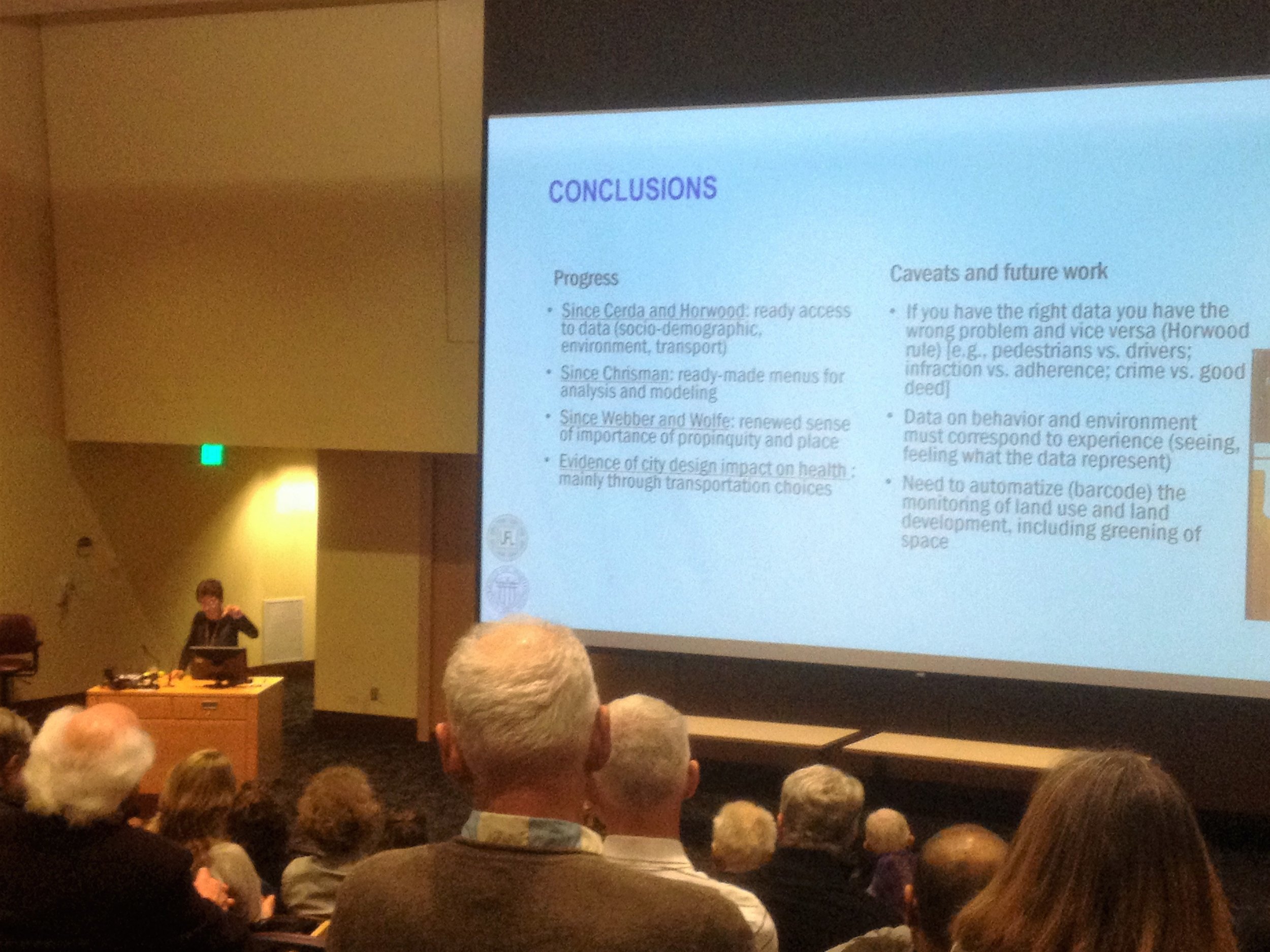

The Department held a celebratory final lecture and cocktails event this past Saturday in her honor. Current professors, former colleagues, and past students listened as Anne gave a brief whirlwind history of a subject near and dear to her — the collection and application of data on urban life to influence how we can improve our cities and ourselves.

Professor Moudon delivering her closing remarks | photo by Josh Janet

She first spoke of Ildefons Cerdà, the world’s first urban planner, who expanded Barcelona in the 1850’s with the Eixample district to address mass health issues due to overcrowding. Cerdà relied on data collected on myriad subjects — from the sizes and lengths of streets to the volume of air one person needed to breathe — to inform the development of the new district. The Eixample isn’t all that well regarded by architects with regards to urban form — there are little to no landmarks in the district and the grid layout is monotonous as a result — but Cerdà’s 1867 publication, “General Theory of Urbanization,” was the first of its kind in developing the new field of urban planning.

Aerial image of Eixample | Images via Amusing Planet

Anne continued with the innovations of Sir Patrick Geddes, the Scottish planner who developed ideas related to regional urban planning and “conurbation,” or the continued urbanization of areas beyond central cities, in the early 19th century. He developed the “Valley section model” as a representation for how regional environmental characteristics shaped city institutions and values.

The “valley section model” created by Patrick Geddes | Images via Wikimedia commons

Anne finished with the Puget Sound region and the advancement of geographic information systems (GIS), beginning with the founding of the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA) by former UW professor Edgar Horwood in 1963. Horwood, a civil engineering professor, was fundamental in the guiding of information system development for urban and regional applications. We would not have complex mapping software like ArcGIS today if not for Horwood’s foresight and leadership.

The use of data collection for the advancement of city planning is an obvious fit, but it got me thinking about the lack of data collection for architecture. Our work is so site and client specific that it is difficult to apply broad ranges of data sets to our designs and applications. We innovate where possible, of course — we listen to clients’ needs and may research what new technology or materials may exist that can address lighting, energy, or durability concerns (assuming it falls within a normal budget).

At Urbal, we also regularly update our senior housing programming based on the information that we receive from clients, who make their suggestions based on the data they collect from their residents and staff. These can range in scale from the size of certain spaces, like a Wellness Center, to the location of the control valves in roll-in showers.

Architects have to strike a precarious balance between pioneering new and/or untested building systems, materials, and programming arrangements, and chasing the zeitgeist with outdated technology and modes of thinking. We also face the prospect of being replaced by computers, if companies like Flux (an offshoot of Google X) are able to truly integrate the complex web of zoning codes, building codes, accessibility codes, structural codes, fire codes, and mechanical/electrical/plumbing codes into a single development tool. I remain skeptical (if perhaps just a little biased) that any computer system can replace the need for a design team, but in honor of Anne Moudon’s insistence on the need to automatize land use development for urban development, I’ll try to keep an open mind.

Sources:

- Bausells, Marta. “Story of Cities #13: Barcelona’s unloved planner invents science of ‘urbanisation.’ ” The Guardian. 1 April 2016. Available WWW: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/01/story-cities-13-eixample-barcelona-ildefons-cerda-planner-urbanisation.

- Marshall, Victoria. “The Valley Section.” City in Environment. 16 February 2013. Available WWW: http://cityinenvironment.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-valley-section.html

- Dueker, Kenneth J. “Edgar Horwood.” URISA. Available WWW: http://www.urisa.org/awards/edgar-horwood/.